|

Storms

are dangerous. They can kill and they often do. This is not a

general description of storms but a few selected topics from

wartime flying, gliding, some background philosophy and some

personal experience. Maybe some lessons for the thoughtful.

There

is a monument at the entrance to

Carnarvon

National Park

- an aircraft wing standing upright. It is from an American

aircraft - metal as we use today - that was wrecked by a storm

on a simple cross country flight in our outback. All killed.

And such an aircraft would have a higher

strength than, say, a 747: That is, put rather crudely,

a higher G load to structural failure. Be it a Spitfire, a

glider, a modern airliner - storms can always win.

They often do.

Storms

are simply one aspect of weather and as such should not be too

separated from our understanding of weather generally. Storms

can be forecast - or mostly they can be - but forecasting can

be imprecise or faulty, or simply unavailable. Nothing can

replace experience but we cannot always decide upon the

experience we should have. Storms themselves vary. They can be

isolated, in lines, associated with weather patterns,

triggered by physical features, be the so called ‘dry’

variety, spawn tornadoes, have low cloud associations or show

surprisingly little cloud, vary in colour leading up to the

terrible brown storms, have associated with them the smoothest

of lift or be turbulent to structural failure, have invisible

(or wonderfully visible) rolls - and so we could go on.

Storm

characteristics do vary with the part of the world we are in.

If we take the ‘gliding’ area west of the Divide from The

Downs to

Victoria

we can certainly

have storms but they are not normally a real worry to the wary

glider pilot. Go further west and north into the tropical or

monsoon area and we have - well - the monument at the park

entrance. There are of course storms in

England

and

Europe

and they can be

severe but usually they are not in comparison with elsewhere.

During the war there was the incredible effective ( from our

point of view) firestorm series of bombing raids on

Hamburg

. Potential for storms. Potential for firestorms from

concentrated bombing as

at

Hamburg

and later,

Dresden

. First night at

Hamburg

and conditions suited the bombers. Next night the storms

played merry hell with the aircraft but not quite, in most

cases, to the structural failure stage. And, it is said,

storms were only to about 20,000 feet. Babies, in comparison

with the 80,000 plus heights of elsewhere. If we move to

USA

we now see on TV the terrible storms and lightning and

tornadoes they

have in the central west. I will save the Asian monsoons for

later.

For

an understanding of storms a pilot needs theoretical knowledge

of storm formation and structure - an understanding of lapse

rate - of the dry adiabatic lapse rate - of condensation

level- of weather pattern movement. Then of course for the

storm itself we have ice, hail, lightning. Updraft and

downdraft. The smooth outflow and lift area, turbulent areas,

the roll area or cloud. But all this should fit into a general

weather knowledge. Limited knowledge can be dangerous.

The

fortunate pilot is introduced to storms gradually - later,

actually, after a knowledge and appreciation of weather has

already been built up. Luck of the draw in a way - and I made

a very lucky and interesting draw. Let me expand. I began by

doing over a year of training in roughly what I have described

as the gliding area. As it was training many weather decisions

were made for me and as I gained training experience I was

exposed to more and more weather. But rather soft weather.

Then the move to

England

and another year or more of further training and actual first

pilot experience. A vastly different type of weather that

introduced me to bad weather flying but not really of the

storm type. A background weather experience that served as a

suitable introduction for what was to come later.

Let

me leave storms for a while, and

move to the pilot. A pilot of course needs training and

experience. Training is not experience - experience comes

later: But in most cases even experience has its limitations.

And the weather in which a pilot flies has its patterns quite

apart from what we might call the regular

local climatic patterns. But let us move to real life.

And a few

comparisons or stories.

Waikerie

South

Australia

. World competition glider pilots. One from

England

. In conversation he mentioned - the village to the east about

twelve miles away. Twelve miles? No - it was about forty. He

was judging with his very extensive English flying experience.

But don’t let us only pick on the Poms. Wartime. Wartime

trained pilots with eight full months of

training. Air Force pilots with wings. Air Force

training - not Saturday afternoon flying. On a number of

occasions I would have my little joke with them when as

instructor I would take them up on their first (air

experience) flight in

England

. A look at the English countryside. Experiencing a new

aircraft type. A typical very hazy English day. Almost a fun

flight. I would end them up on the downwind leg with the aerodrome

in position on their side - correct heading - correct height.

Then tell them -

right, we’re in the circuit. You try the landing. Quite

often they simply could not ‘see’ the airport. There it

was large as life and their unaccustomed eyes could not

‘see’ it through the incredible complexity of the English

countryside after the sparse easy to follow Australian

countryside. But in no time flat they would be quite at home

flying in

England

.

These

pilots were not over-confident - exactly the opposite. English

countryside was a new and surprising experience - the

countryside and the poor hazy

visibility. Overconfidence even when combined with training

and experience can be another aspect. A thousand hours of

flying in

England

with its confused countryside, its smoggy conditions when on

occasions the ground becomes invisible from 3000 feet, its low

cloud base of a hundred feet. Then to

India

- what are these local pilots on about with weather after

English weather? The pilot I am thinking about (and it was not

me) did not take long to learn.

Another

aspect before we get back to our storms. There is a certain

‘in between’ condition when

we consider area climate and short time

associated weather variability. We can have what I will

call periodic weather. A dry spell of quite a few years. Wet

periods.

In

the sixties we had a number of successive years with specific

storm conditions over the

Downs

and the South-East. Doubtless even beyond as well. As summer

approached the weather was often stormy. Afternoon, fairly

scattered isolated

or line storms. We ‘learned’ certain habits. Watch things

on cross country flights but some very interesting cross

country flights were still possible. Carry on with the

training circuits but be ready to pack up quickly and get the

gliders hangared. For an hour or so at least. We developed a

‘safety’ procedure. Most storms were pretty obvious -

nothing unusual about that - but I can recall two days when we

had what I will call dry storms. The weather change was there

to see but - well,

it didn’t really look like a storm. But on two occasions a

glider doing a circuit suddenly found it was being ‘blown

down wind’ and simply could not complete its circuits. Blown

away before the ‘storm’ and luckily, in both cases to a

paddock landing a few miles away. But more detail on those

flights shortly.

And

something else too. When to pack up and hanger the gliders?

I recall once at Oakey when

Daphne and I were flying the Hutter privately and the

Oakey Club were doing club flying. Yes, storms about but not

yet time to pack up. Or was it?

Local knowledge told the Club members that a certain

storm would miss the aerodrome.

But they were neglecting one recently published bit of

knowledge. I knew of it and put the Hutter away. They

continued to rely on their “local experience’ and as a

result had their glider damaged trying to get it off the field

and into the hanger when

the storm did pass over the aerodrome itself.

My ‘extra’ piece of knowledge came as a result of a

series of experiments carried out by the Met section of the

Department of Civil Aviation - storm experiments on the

Darling Downs. I will move on to that too

but one final bit of general comment.

The

sixties moved on and the stormy

weather cycle moved on too. A new generation of glider pilots

grew up who had little ‘storm’ experience and almost

laughed at us old timers who warned of a storm danger when we

saw such a danger as a possibility. The ‘new’ pilots had

to learn the lessons for themselves. I don’t recall saying

though - ‘Told you so’. What is that background word so

important in the education of a pilot? - AIRMANSHIP - a broad

and very important concept. Anyway, lets move to the Downs

Weather experiments. That will get us back to storms

themselves. “Glider weather’ first and wartime later.

Gliding

Weather:

It

could be a good day. Isolated fair weather Cu or better still,

maybe it could be streets of these Cu. Maybe very smooth -

perhaps a little rough. Depending on the lapse rate picture we

could also have towering Cu. Not thunderstorms but tops at

12, maybe 15, maybe even over 30,000. Again, smooth or

rough but this

not specifically related to height.

Turbulence can vary. I can recall one fantastic day

approaching Narromine from the north where I took only about

every third thermal, one turn and I was centered on smooth

1000fpm lift. And the opposite - again in the clear - when I

could demonstrate to a pupil how almost ineffective the

controls could become under a good Cu - and of course worse if

we had illegally gone in. There can be terrible turbulence in

a Cu at, say, 12000. But again, I can recall a climb in a

towering Cu near Inverell where the lift was smooth. And

powerful. I had elected to come out at about 20,000 and turned

on to my pre planned escape heading. I gained another 3000 on

the way out and saw the tops were over 30,000. Why not go

higher? Basically then there were two types of oxygen masks. I

did not have the ‘better’ type recommended for 30,000 and

above. But we are really concerned here with storms. Storms

can look bad but they can also be deceptive in appearance. I

will recount now an extract from a write-up I did in the

sixties. It was called Sailplane Meteorology -- without tears.

Late

evening storms had been forecast. Throughout the day, although

there had been an abundance of ragged Cu, lift had been very

weak. Even the Grunau, which can usually stay up on a puff,

managed only a bare twenty minutes. The ground was very wet

from almost a week of rain.

About

4pm the Hutter was launched, after the Kookaburra had done a

circuit without contacting lift. Those at the aircraft end

noticed a heavy cloud to the left with a misty scud in

turbulent movement well below the main cloud base. Those at

the winch saw the pilot contact lift to the right near a

similar but separate cloud. It soon became obvious to them

that the pilot was having great difficulty controlling the

aircraft. About this time those at the winch end heard a sound

like rain and saw trees and corn in the distance in violent

agitation. Soon the wind (for wind it was and not rain)

arrived. It blew at 25-30 mph almost down wind compared with

the launch direction. This immediately and effectively stopped

launching. Meanwhile the Hutter got further and further away

and eventually was seen to make an approach into a paddock

about four miles from the strip. To this time there had been

no thunder, lightning or rain. Within the next hour small

isolated storms passed through the district in fairly rapid

succession, but no rain fell on the aerodrome or where the

glider had landed.

Another

time. The sailplane pilot reported smooth and increasing lift

off the launch. This lift suddenly became turbulent and scuds

were noticed forming at the sailplane height of about 2000

feet. Turbulence became so severe the pilot was barely able to

maintain control.. The ‘g’ meter, fitted as a permanent

instrument to this aircraft, fluctuated between -1.5 and +3 g;

dust remained suspended before the pilot’s eyes. He noticed

the strong wind change and turned down wind out of the

turbulence, drifting rapidly away from the field. Several

later attempts to return again produced severe turbulence and

it became a case of getting down somewhere in a paddock. This

sailplane was not equipped with spoilers and the pilot found

himself in the unusual position of being unable to lose height

even with as much speed on the clock as he dared.

Paddock after paddock disappeared beneath him, and

after quite a few beats across wind at 800 feet, a safe

landing was made. The

pilot reported it was his most frightening flight ever. ( I

was not the pilot on any of these flights!)

Next

day, at about 1.30 pm three heavy storms could be seen from

the field. The Grunau was soaring and as one storm seemed to

be approaching the aerodrome all aircraft except the

Kookaburra were hangared. Very heavy rain looked 6-8 miles

away when the wind changed, thus preventing the launch of the

Kookaburra. The Grunau at this time was about 1500 over the

strip. It lost height slowly and looked to those on the ground

to be setting up for a ‘normal’ circuit, which would have

meant a 25 mph downwind landing. At about 300 feet he made a

change of direction and even though it was obvious to those on

the ground control was difficult, he made a safe landing into

wind. The pilot

reported that at first he thought

he had found a smooth evening thermal but turbulence,

when it came, had him afraid of structural failure. His

concern was to try to get down safely - anywhere.

On

another occasion the Kookaburra launched with a storm nearby.

Those on the ground noticed a strange wind change when the

plane was about 200 feet. The pilot reported a normal launch

into lift and an immediate climb to 3000 feet. The previously

smooth lift then became turbulent. He applied spoilers, lost

height rapidly, and landed safely in the strong wind period to

the commencement of heavy rain.

These

few years of peculiar storm conditions passed and as I said

earlier, later pilots 'poo-hooed' advice of the lessons

learned. What are the lessons? Let us look now at what I will

call - The Anatomy of Thunder Storms.

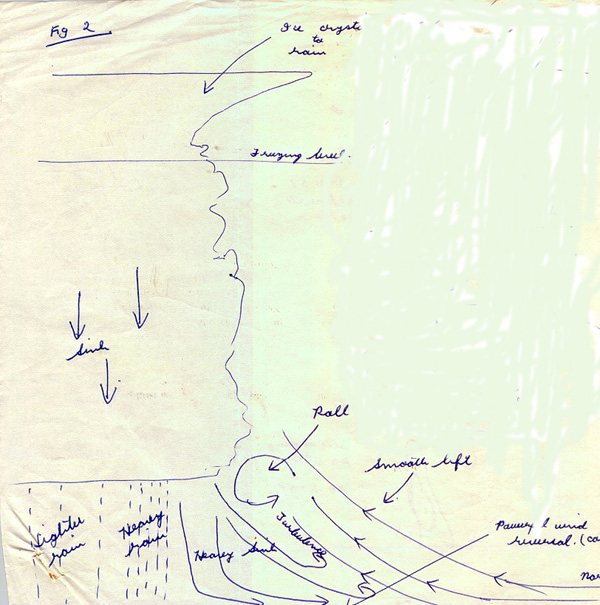

Our

representative storm cell has grown out of a towering cumulus

cloud with its cauliflower top. An anvil blows out ahead of it

at the top gradually shading the area ahead. The whole cell

moves across the countryside blown by a lower but also upper

wind. It has grown well above freezing level which will vary

mainly with latitude but also with atmospheric conditions. On

the Darling Downs it will often be about 12,000 feet. There

will be a strong area of lift inside the cloud itself and

behind that a downdraft area. The updraft and downdraft will

be essentially side by side. In

India

we were quoted possible speeds of 100 mph. I have seen that

figure corrected after later post war research. Two hundred

miles per hour was given.

On

the ground ahead of the cell the wind will often be light

blowing towards

the cell. Thus aircraft can be taking off into a light wind

flying away from the storm. Suddenly though there will arrive

an extremely powerful and turbulent downdraft wind ahead of

the cell. A wind reversal as far as the pilot is concerned.

Just ahead of the cloud itself at about cloud base these two

opposing winds can form a roll. Though usually invisible at

times it can appear as a most spectacular roll cloud. And this

- visible or otherwise- can

be catastrophic for a pilot. Once a pilot has actually

seen a roll cloud he needs no further advice on the dangers

near storms.

The

diagrams that follow are from notes written in the sixties -

line drawings from research information - and obviously before

the days of electronic reproduction.

|

|

|

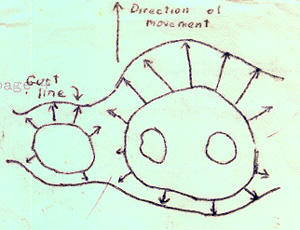

The

diagram on the left shows part of a squall line, as opposed to

a single cell, with the wind direction shown.

The first gust line preceding a line of storms may

extend for many tens of miles without a break.

|

|

|

|

Radar

picks up cells from which rain is falling.

The two diagrams

below show actual radar echoes for a squall line and random

storms ...

Recent

investigations were made into storms on the Darling Downs by

the meteorological Office, Brisbane. While it would be unwise to apply the findings ‘as is’

to all areas, many findings will hold good as a general rule.

Of about 100 storms studied, one fifth occurred in

general rain conditions and as such would not normally affect

the sailplane pilot. One fifth had short paths of less than 20

miles, but about

half had paths of more than 20 miles.

Locals

will often say, "our storms come from that direction" or

"any storm you

see there won’t come here". The Darling Downs investigation showed

that almost all of the 100 storms studied did come from a

certain 120 degrees of the compass (in this case 180 to 300

degrees).

The investigators were naturally reluctant to draw

definite conclusions from such a short series and they did

draw attention to the fact

that ground estimates of paths are frequently

unreliable. An attempt was made to relate storm movement to an

upper wind level. In work done in

Florida

in 1949 over 95% of storm movement agreed with the 12,000 foot

wind. Agreement on the Downs with winds at

Brisbane

(nearest available) also

gave a high agreement but at a lower percentage with the

10-15,000 foot wind. Speed of storm movement was slower than

the wind speed.

From

the rainfall results of actual

random type storms it appears most are 4-10 miles wide. This

points to the fact a glider may be able to make a safe landing

to one side of the storm. In the figures below, rainfall

results show the extent and path of random storms. Gliders

could be doing cross country flying in such storm conditions.

Obviously a storm may consist of more than one cell. A number

of cells may form one large cloud and the life of the cloud

may be prolonged, with each cell having a life of about half

an hour.

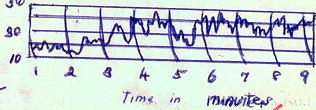

While

people usually associate the arrival of a storm with the

commencement of heavy rain, the storm has arrived, as far as

the sailplane pilot is concerned, four to ten miles ahead of

this, and 15 to 20 minutes before.

|

| Smooth lift is experienced

at height before those on the ground become aware of the wind

change. When lift is experienced the ground is often in full

shadow. Because of the cell cycle danger can exist well before

the advent of thunder or lightning. It is repeating the

obvious to say that the roll area is a source of high danger

whether it is cloud visible or not. |

|

|

|

|

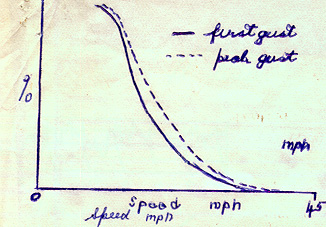

The

wind reversal, when it comes, can be sudden and strong. Ground

handling is difficult. The diagrams

emphasise the first gust danger and its severity.

|

|

I will conclude this section with some extra findings of the

Darling Downs storm observations. During a 127 day period there were

56 storm days. Of these 32 were line storms, 6 were along

surface fronts, 19 were ahead of surface cold fronts and 7

apparently had no connection

with surface fronts. In the squall line zone ahead of

the cold front, several roughly parallel lines of storms were

observed, although it was not found possible to distinguish

the lines from the ordinary synoptic weather charts. The lines

examined had an average length of over 100 miles and were 36

miles wide. The squall line is not always parallel to the

front line and of the cases examined varied up to 60 degrees

from the front line. The

squall line may persist for up to 24 hours and move hundreds

of miles in that time. The squall lines consist of cells as

described previously.

But

let us leave peace time Australia

now and go back to the World War II period.

Wartime

Weather:

Of course there are storms in

England

and

Europe

. On very rare occasions

England

can have a tornado. But I will put English ‘bad weather’

into context this way. After the initial shock of experiencing

average English weather after the ‘nice’ Australian

weather we trained in, many of us grew almost to like the poor

visibility hazy days. Those of us involved with Beam

instruction (landing in low cloud conditions using radio beam

systems ) literally rubbed our hands in glee when we struck a

‘real’ day with a cloud base of 100 feet. But after

falling in love almost, with

the bad but soft English weather we entered a new world with

the weather of

India

and

Burma.

Almost

a thousand hours of wartime

England

first pilot. Flying a Mosquito from

England

, across North Africa, and into

Asia. Then the initial Squadron

briefing at Calcutta. Forget about previous weather experience. Soon, it will be

the monsoon. Rain you’ve never experienced. Well, yes, very

heavy. It will take the paint off your aircraft. And peel the

fabric cover over the under wing top surface. But that will

not be the real worry. There will be storms. Long lines along

the coasts you will have to cross going and coming - Burma,

the Malay Peninsula. And other storms as you fly over Siam

and perhaps China (no storm detecting radar in those days.)

You enjoy cloud flying? Well here you stay out of cloud if at

all possible. Your aircraft that will take you easily to

40,000 feet won’t get you over them and will break up in

them.

We

were told we would not be able to tell the difference between

blue sky and black cloud. Maybe, we thought but it was right

and it did happen to me. I was pretty sure it was a clear

space in the distance to use but no - it WAS black cloud ...

and

worse still, we were told, was the brown storm. Later I was to

agree with that. We were also told of the Spitfire pilot who

entered a storm and found himself in his seat with no aircraft

round him. He did parachute

down OK, we were told. A good story we felt, and obviously

embellished to impress. More on that story later.

So

the monsoon came and so did the weather and the storms. I will

quote now a number of extracts from my wartime write-up -

"This

Man’s War".

19/4/45

... I noted in my diary: F\Lt........... did not arrive

from Cox’s. They searched with

the Harvard in the morning. We are on tomorrow. We flew low as

prescribed searching, two miles south of track but no sign.

Time for a swim. The

Squadron was based at Alipore, Calcutta

. After a briefing we would take off some time after lunch and

fly to an aerodrome on the coast to be ready for a trip (an op

as it was called) the next day. We used a forward base, and

this shifted forward as we gained ground against the

Japs. At this time we used Cox’s Bazaar, in present

day

Bangladesh

. If we were early enough we could go for a swim in the

Bay of Bengal

. We would fly our op

and, after refuelling, would return to Alipore. This out and

return section was across the Sundabans, the 300 mile wide

delta of the Ganges and Bramaputra Rivers - flat, swampy,

mangrove covered, settled in a few isolated spots. We each got

to know certain islands and spots on track on this run. By

this time - April - storms were beginning to worry us - make

us alter course to avoid them.

20/4/45

... again from my diary: No. 9. Off just after six. There was

a little stratus on the way. It was clear over

Bangkok

for the bomb damage assessment. The Liberators had paid

Bangkok

a visit the day before. Smoke rising but got

Bangkok

OK

. Then we followed a

canal, photographing it, and

also took a bridge for BDA. No

good for mapping survey. We took coverage for map making which

had to be in the clear from 25,000 feet. Saw what looked like

a dump and took it from 9500. Alto-stratus clouded over 10/10.

It was 10/10 then, not 8/8 as now. Time 6.50.

After

refuelling at Cox’s,

I flew back to Alipore with the weather very stormy

indeed. ‘Very stormy indeed’

was quite an understatement. It was one of those

‘brown storms’ we had been warned about. Hell, it looked

terrible, and right on our track. I deviated east and flew around

it.

Next

I got involved in flying the C.O. to

Kashmir

for leave. I was one of the second dickies. That took a couple

of days. Meantime the wreck of the missing plane had been

found. There is a common saying for someone who is exactly on

track - dead on track. Unfortunately it was for real this

time. It was on a mangrove island that had a particular shape

and one some of us used to check our track.

29/4/45: I did an

op to

Southern China

flying there direct from Alipore and landing at Cox's on the

way back to refuel. Between Cox's and base we had a look at

the wreck. It was hard to spot but we knew exactly where to

look. It did not look as though he had been trying to ditch as

the aircraft faced inwards under the mangroves just off the

water’s edge. It appeared remarkably whole.

Many

years later, after gliding experience, maybe the penny dropped

about this prang. It was exactly where my brown storm had been

but one day different. Glider flying at competition level

entails weather knowledge. I noticed this -- Similar weather

patterns regularly occur. With many weather patterns Cu clouds

and Cu Nimb clouds are part of the pattern. I noticed that

such clouds tend to form in exactly the same place. Of course

such clouds grow and die - but often in the same place. One

turning point may consistently be bad while another will have

helpful lift or clouds above. Common weather patterns in

exactly the same place. Today could be the same as yesterday -

or tomorrow. So there is a chance he got mixed up in a brown

storm perhaps just

at formation stage. Such a cloud could literally flatten an

aircraft against the ground. Perhaps we are moving into the

post war micro burst situation.

Back

to wartime. So I watched storms as the weather (and the

storms) got worse.

17/5/45

... a diary comment: Had a

bad time in a storm. Maybe he doesn’t treat them with as

much respect as I do.

12/5/45

... a diary comment from an op: Off

to Bangkok

again with a lot of cloud on the way. Some along the Burma

Peninsula and the largest Cu Nimb I have ever seen. I was at 33,000 and

I wasn’t even half way up it.

4/6/45

... my diary write-up for

another op: Rain

in the night so slept in a little. Saw flying control and

arranged to take off from

the short runway using the extra 200 yards of taxiway. It went

quite OK. Full load and 25 degrees of flap. Also we were

taking off over the sea. We were forced to climb in the wrong

direction - back towards Akyab and then go well south steering

210, 175, then 100 degrees. Crossed the delta and at 20,000

were getting ice in the stratus.

Struck a wall edge of Cu Nimb from a front along the

mainland so we gave it away. Used

headings from Akyab and set course for base.

Paint (dope) and fabric strips over the ply peeling off

the wings. Didn’t like it.

25/7/45

... another diary entry: Fourth wedding anniversary - what a day.

It rained from 2 am till 8. Seven inches and the aerodrome

unserviceable. The op. was therefore off. Rained off and on

all day. There was a worried Spitfire pilot. He flew through

bad weather and when he landed saw his prop was in a mess.

Apparently the five bladed prop is wood with a fabric

and hardened dope cover.

It was all in tatters.

26/7/45:

Tried to get

off in the afternoon but another Spitfire pranged and blocked

the runway.

Will try to return to base tomorrow.

27/7/45:

Off at 9.15

and needed all the runway, just clearing the trees. Fabric

coming off the wings. Showers all round but weaved in between

them. We were able to climb and every now and again sneak

through gaps. Turned the transfer cock on and blew 200

unwanted gallons from the drops. From my navigator’s plot we

flew 270, 180, 330, 265, 360 to make a track of 300 degrees.

Got back OK. And so the flying goes on.

Bad

weather flying but I avoided the storms. Some did not. I will

conclude with two other episodes.

Many years after the war I

found written up in a book the episode of the Spitfire we were

warned had broken up in cloud. I will now quote it and add another storm flight from Burma.

From

"Above All Unseen" by Edward Leaf 1997 ISBN 1 85260 528 6 page

160 ...

as he returned to Chittagong from a sortie over central

Burma W/0 EDC Brown of the RNZAF flying a 681 Squadron

Spitfire PR IV was faced with a mighty bank of cloud. With insufficient fuel to fly around it, he had no

option but to dive straight through it.

Having gone into a spin and blacked out, W/0 Brown

suddenly found his aircraft disintegrating around him. Somehow he managed to pull his ripcord and land safely

but it was later found he had fractured his spine.

From

the magazine "Mossie" No.26 Summer 2000 at page22

... a

report by Squadron Leader C. L. Gotch of 82 Squadron operating

Mosquitos out of Kumbhirgram (Assam,

India) ...

To reach the

operational area, the

Chin Hills

rising to 9000 feet had to be negotiated first. The clouds over the mountains were just one of the

hazards. On

the night of 10th February 1945, I took off on an operational

sortie at 2000 hours. At

briefing we had been warned by the Met.

Officer that the weather was not good and that on no

account was it safe to enter cloud.

... this

instruction was always

difficult to accede to. Knowing

that I had to climb to approximately 15,000 feet to climb over

the cloud tops, I decided to make height over base to at least

10,000 feet. It

was a dark night with no moon, but seeing some broken patches

above, I tried to find a gap through which to climb. At

8,000 feet while heading for a gap I found myself in

cloud without warning. The

bumpy conditions were immediately so severe, that I had no

apparent control of the aircraft.

Relying solely on instruments, I saw that the

artificial horizon was showing the aircraft upside down. I carried out the normal correction as best I could. The aircraft then stalled, the ASI showing 80 mph and

the rate of dive 4,000 feet per minute. What happened next is extremely confused, but after

being in cloud for not more than two minutes I found myself in

a gap at 13,000 feet with the cloud continuous above me to at

least 16,000 feet.

Seeing

the airfield lights below, I dived immediately, and landed

straight away. I

consider myself extraordinarily lucky to have come out of the

incident alive. Just

before coming out of cloud I had told my navigator to prepare

to bale out as I had no control of the aircraft at all.

I have

given strict instructions to all aircrew in my Flight not to

attempt to fly near cloud at night and on no account to enter

Cu cloud at any time during the day or night.

|